A Picture of Gratitude

Feb 6, 2024

How can I find a gift meaningful enough to thank the people who saved my life?

That’s what Gary Teman, 59, asked himself a few weeks into treatment for prostate cancer at Adventist Health Portland.

“I thought, ‘I appreciate these people so much,’ and there’s not many ways to show it, you know? I’m not gonna tip ’em five bucks,” Gary says. “I wanted to find a way to thank them. I thought, ‘What am I gonna bring on my last treatment day? A box of chocolates? How can I tell these guys that I really love ’em and appreciate ’em?’”

When that final treatment day rolled around, Gary did bring a small box of chocolates as a token of his appreciation.

But that’s not all. He also brought a gift large with meaning: a work of art custom-crafted from the heart.

PSA? Say what?

After 40 years cleaning and installing carpets, Gary’s knees and back were shot. With a limited income and no health insurance, he couldn’t afford medical exams. So when he got sick or had minor injuries, he just toughed them out. After switching jobs to driving for Lyft in Portland, he found out he qualified for state health insurance.

“I hadn’t been to the doctor for 20 years, so I finally went in for a checkup,” he says. “She did blood tests, and I had a little blood pressure and cholesterol issue but not bad. Then she said, ‘This PSA reading is a little bit alarming.’ At first I was like ‘PSA? What’s that?’ But I quickly figured it out.”

PSA, or prostate-specific antigen, is a protein produced by the prostate gland. The blood level of PSA is often elevated in men with prostate cancer, although several noncancerous conditions can also cause PSA levels to rise, according to the National Cancer Institute.

In Gary’s case, his PSA level did indicate cancer. And when he followed up with a urologist, he found out the cancer needed treatment.

“They said I had two options,” Gary says. “One was to remove my prostate completely, and the other was to have radiation therapy. Both seemed scary to me.”

Facing a tough choice, Gary researched both options and decided to go the radiation therapy route with Dr. Aaron Hicks, radiation oncologist with Adventist Health Portland. Looking back, he’s glad he did.

From X-rays to acrylics

“I found out quickly that I was in good hands,” Gary says. “Immediately, I felt my apprehension and fear melt away. There’s something about Dr. Hicks; he’s soft spoken yet he’s also direct. You have great confidence that he’s good at what he does.”

Gary describes Dr. Hicks’ genuine nurturing style that made him feel cared about. “He’s not trying to hurry. And the team he’s got there — they make it a point to let you know they’re human beings also,” Gary explains. “I just felt somehow that I was gonna be okay.”

For Gary’s treatment, Dr. Hicks used external beam radiation therapy, a technique that targets tumors directly with high-energy X-rays. The therapy is given in a series of treatments to let healthy cells recover and help make radiation more effective. Gary’s treatment course lasted six weeks.

As the weeks went on, Gary started to realize that he was a key part of his own treatment team. Not only that, the medical staff genuinely cared about him. They even started to feel like friends.

“About four weeks into treatment it hit me: The best thing I could possibly do is put the energy, creativity and time it took into making a gift they could remember,” Gary recalls. “So I secretly started a painting.”

All about the personalities

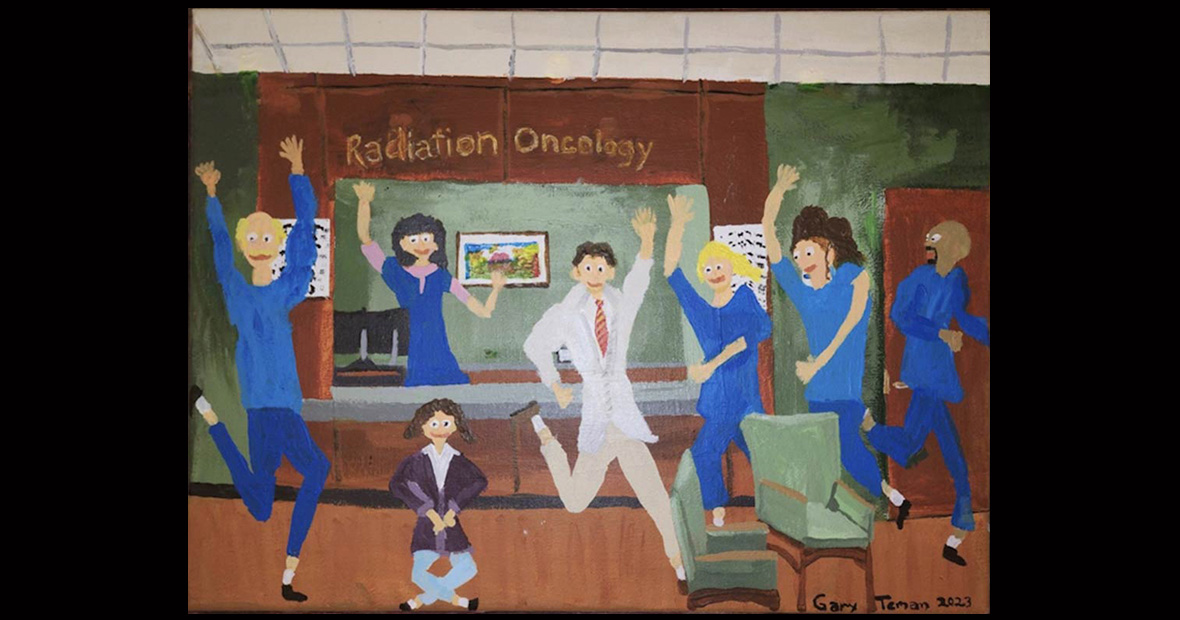

First, Gary snapped a photo of the reception area. Later, he painted that background on a canvas with acrylics.

For the next two weeks, at each appointment Gary studied the staff and made mental notes about their faces, hair, clothing, physical features and expressions. Then he’d go home and paint them as he pictured them, but with an exaggerated lighthearted twist.

“I can’t make a lifelike image of anyone, so I make my version of them,” he says. “It always ends up fun. My figures are usually dancing or being goofy in one way or another.”

Legs, feet, torsos, arms and hands took shape first, then heads and faces appeared on their designated bodies. That brought the portrait to life.

“It really was about their personalities,” Gary explains. One person, for instance, gave Gary an extra dose of courage on his first day when he was overwhelmed. Another wore a braid in her hair in solidarity with Gary, who sometimes braids his own hair and adds beads.

“It was so weird, but at the end of the six weeks I was bummed out that it was over,” Gary says. “I really enjoyed seeing these people every day.”

As treatment ended and the last brush strokes went on the portrait, Gary realized the canvas needed a frame. So he bought tools, wood and stain and built one. “That’s the first frame I ever built,” he says.

All the effort paid off, he says, when he saw the expressions on the faces of those he’d painted.

“When I brought the painting the last day, they all went, ‘Oh that’s me!’” Gary says. “I wondered who might take it home, but right away they found a spot to hang it there on the hospital wall. That really sealed the deal and made me think it was all worth it.”

Hope bounces back

Gary says he will be deeply moved if his painting brings some cheer or extra confidence to other cancer patients. A cancer diagnosis can be very difficult, but, for Gary, hope made a difference.

“I would say try to just have a little hope,” Gary says. “Understand that when you put out positive energy, you’re gonna get some positive energy back. There’s just no way around it. And if you’re around Dr. Hicks’ team, your positive energy is gonna go a long way. It’ll come bouncing back at you.”